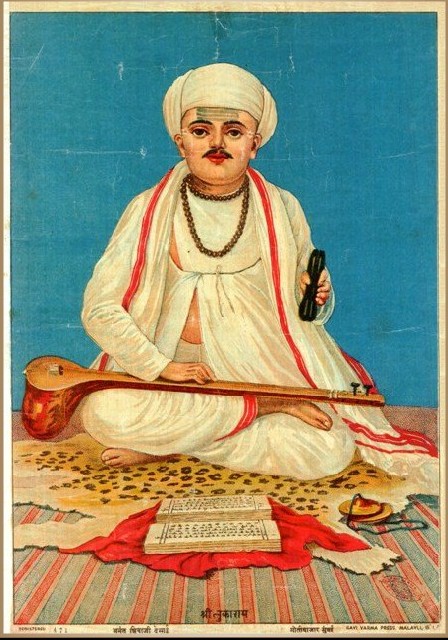

Know About Sant Tukaram, Teachings, Life, Death, Family, Read Full information in English about Saint Tukaram Maharaj full Biography at Who is Identity.

Who is Sant Tukaram

Sant Tukaram Maharaj, also known as Tuka, Tukobaraya, and Tukoba in Maharashtra, was a 17th-century Marathi poet and Hindu sant. In Maharashtra, India, he was a Sant of the Varkari sampradaya. He was a follower of the Varkari devotionalism tradition, which was egalitarian and personalised.

| Name | Sant Tukaram/ Tukobaraya |

|---|---|

| Born/Birth Place | Tukaram Bolhoba Ambile Either 1598 or 1608 Dehu, near Pune Maharashtra, India |

| Death Date/Place | Either 1649 or 1650 in Dehu |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Known for | Abhanga devotional poetry, Marathi poet-sant of Bhakti movement. |

| Wife Name | Rakhama Bai, Avalai Jija Bai |

| Mother Name | Kanakar More |

| Father Name | Bolhoba More |

| Sons | Vithobā Nārāyan Mahādev |

| Teachings | Read here |

Tukaram was born in the current Indian state of Maharashtra. Tukaram Bolhoba Ambile was his full name. The year of sant Tukaram’s birth and death has been a source of debate and investigation among 20th-century historians. He was born in the village of Dehu, near Pune in Maharashtra, India, in the years 1598 or 1608.

Kanakai and Bolhoba gave birth to Sant Tukaram. More and more historians believe his ancestors belonged to the Kunbi caste. Tukaram’s family was involved in agricultural and trading, as well as retailing and money lending. His parents were devotees of Vithoba, a Hindu god Vishnu’s avatar (Vaishnavas). Tukaram’s parents both died while he was a teenager.

Tukaram Marriages

Rakhama Bai was Sant Tukaram’s first wife, and they had a son named Santu. During the famine of 1630–1632, however, both his son and wife died of starvation. Tukaram became introspective, meditating on the hills of the Sahyadri range (Western Ghats), and subsequently claimed that he “had dialogues with my own self” as a result of the fatalities and pervasive poverty. Tukaram married a second time, this time to Avalai Jija Bai.

Devotional Life

He devoted the most of his final years in spiritual worship, community kirtans (singing group prayers), and Abhanga poetry composition.

Tukaram’s kiratans and Abhangs exposed the evils of the time’s society, social system, and Maharajs. As a result of this, he encountered some resistance from society and some individuals. Mambaji, a man who ran a Matha (religious seat) in Dehu and had some followers, harrassed him a lot. Tukaram initially assigned him the task of performing puja at his temple, but he was envious of Tukaram since he saw Tukaram gaining respect among the villagers. Tukaram was once struck by a thorn’s staff. Tukaram was the target of his nasty language. Tukaram was afterwards admired by Mambaji as well. He enrolled as one of his students. Tukaram vanished in 1649 or 1650 (the date is debatable and has to be investigated).

According to some researchers, Tukaram met Shivaji, a leader who opposed the Mughal Empire and formed the Maratha kingdom; tales surround their continuous interaction. According to Eleanor Zelliot, Bhakti movement poets such as Tukaram influenced Shivaji’s ascent to power.

Sant Tukaram Teachings and Philosophy

Tukaram embraced male and female disciples and devotees alike. Bahina Bai, a Brahmin woman who experienced rage and violence from her husband when she chose Bhakti marga and Tukaram as her teacher, was one of his famous admirers.

Tukaram taught, according to Ranade, that “caste pride never made any man holy,” that “castes do not matter for the service of God,” that “castes do not matter, it is God’s name that matters,” and that “an outcast who loves the Name of God is verily a Brahmin; in him have tranquilly, forbearance, compassion, and courage made their home,” and that “castes do not matter, it is God’s name that matters.” Tukaram’s daughters from his second wife married men of their own caste, prompting early twentieth-century researchers to question if Tukaram himself was aware of caste. In their 1921 assessment of Tukaram, Fraser and Edwards argued that this is not always the case, because people in the West, too, want to marry those from their own economic and social strata.

Tukaram’s acceptance, efforts, and reform role in the Varakari-sampraday, according to David Lorenzen, reflects the wide caste and gender distributions found in Bhakti movements across India. Tukaram, of Shudra varna, was one of the nine non-Brahmins recognised sant in the Varakari-sampraday tradition, out of twenty-one. Ten Brahmins and two people whose caste origins are unknown make up the rest. Four women are honoured as sant among the twenty-one, having been born into two Brahmin and two non-Brahmin families. According to Lorenzen, Tukaram’s efforts at social reform within Varakari-sampraday must be seen in this historical context and as part of the larger movement.

More About Tukaram’s Philosophy

Tukarama mentions four more people in his Abhangas work who had a major influence on his spiritual development: the previous Bhakti Sants Namdev, Dnyaneshwar, Kabir, and Eknath. Tukaram’s teachings were regarded Vedanta-based but lacked a systematic theme by early twentieth-century scholars. According to Edwards,

Tukaram’s psychology, theology, and theodicy are never systematic. He alternates between a Dvaitist [Vedanta] and an Advaitist view of God and the cosmos, leaning now toward a pantheistic system of things and now toward a specifically Providential one, and he does not harmonise them. He doesn’t talk much about cosmogony, but he does declare that God manifests Himself in the devotion of His believers. Similarly, faith is necessary for them to recognise Him: ‘It is our faith that makes thee a deity,’ he asserts to his Vithoba.

Tukaram’s pantheistic Vedantic outlook is supported by late twentieth-century scholarship and translations of his Abhanga poetry.

According to Shri Gurudev Ranade of Nimbal’s translation of Tukaram’s Abhanga 2877, “God, according to Vedanta, fills the entire cosmos. God has filled the entire universe, according to all sciences. The Puranas have clearly taught God’s ubiquitous immanence. The sants have told us that God fills the world. Tuka, like the Sun, who stands utterly transcendent, is playing in the world uncontaminated by it “..

Scholars point to a long-running debate, notably among Marathi people, on whether Tukaram believed in Adi Shankara’s monistic Vedanta doctrine. According to Bhandarkar, Tukaram’s Abhanga 300, 1992, and 2482 are in the style and philosophy of Adi Shankara:

What is it that remains distinct when salt is dissolved in water?

Sant Tukaram

As a result, I have become one with thee [Vithoba, God] in joy and have lost myself in thee.

Is there any black residue left when fire and camphor are combined?

Tuka declares, “Thou and I are the same light.”

Other Abhangas credited to Tukaram, on the other hand, condemn monism and advocate the dualistic Vedanta theory of Indian intellectuals Madhvacharya and Ramanuja. Tukaram writes in Abhanga 1471, according to Bhandarkar’s translation, “The expounder as well as the hearer are tormented and distressed when monism is preached without trust and love. He who proclaims himself Brahma and continues on as normal is a clown and should not be spoken to. Among religious men, the shameless one who proclaims heresy in contradiction to the Vedas is scorned.”

Tukaram’s genuine philosophical viewpoints have been muddled by problems of poem authenticity, the finding of copies with significantly varied numbers of his Abhang poems, and the fact that Tukaram did not write the poems himself; they were written down long later, from memory, by others. Tukaram opposed mechanical rites, rituals, sacrifices, and vows, favouring a direct type of bhakti instead (devotion).